本文刊载于《符号与传媒》总第25辑

2022年第2期 第 44-54 页

导言:尼古拉斯·哈克尼斯(Nicholas Harkness), 哈佛大学人类学系教授、哈佛大学韩国研究所所长,是当今美国符号人类学(semiotic anthropology)研究领域的领军人物。他也是雅各布森年度系列研讨会发起人、哈佛燕京学社符号人类学项目负责人。哈克尼斯教授长期致力于语言、声音、音乐、宗教等方向的符号人类学研究,旨在理解和解释语言与非语言符号活动在文化社群形成与转变过程中所起到的具体作用。特别是,他在皮尔斯符号学基础上,发展并引领的“感觉质”(qualia)分析范式,强调“行为之感觉”(feeling of doing)对人类文化经经验形成的重要性,独树一帜。在本期“符号人类学” 专栏,四川大学赵星植副教授、电子科技大学薛晨副教授有幸采访到哈克尼斯教授。他在访谈中对符号人类学的学科历史、核心要义与发展趋势进行了细致的梳理和深刻剖析。

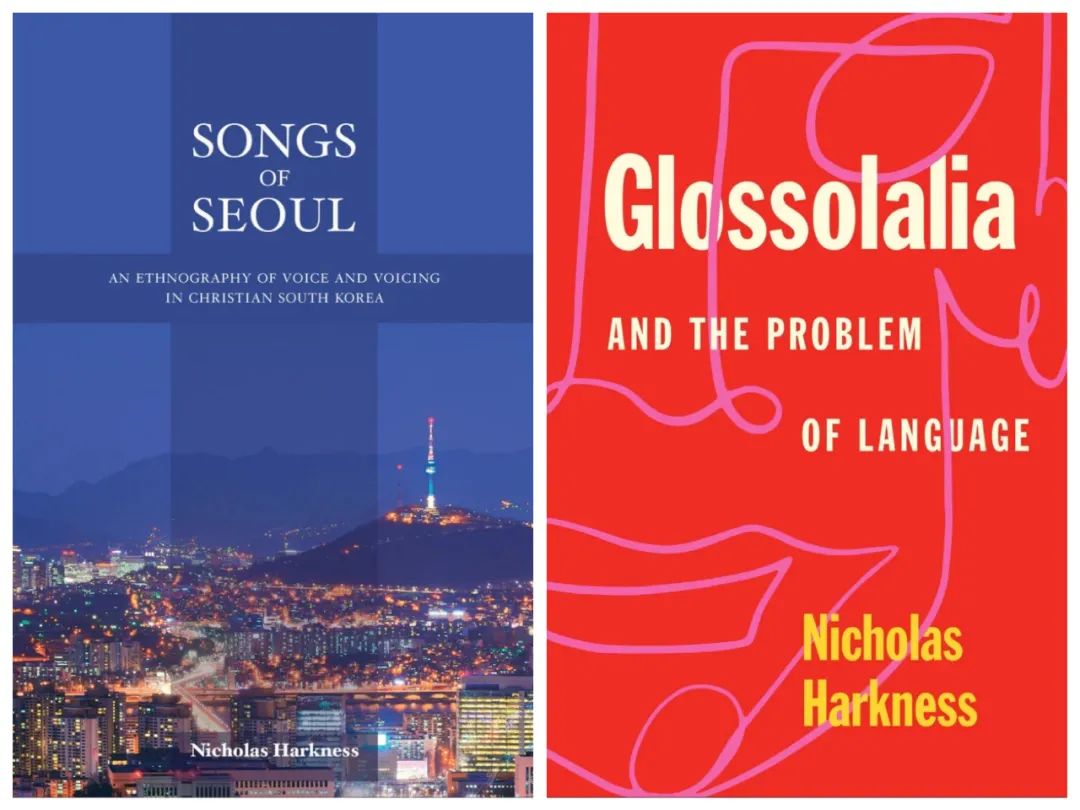

Introduction: Nicholas Harkness, Professor of Anthropology at Harvard University, is a leading anthropologist specializing in linguistic and semiotic approaches to sociocultural analysis and theory. His research in South Korea has resulted in publications on various topics, including voice, language, music, religion, ritual, kinship, liquor, and the city of Seoul. His first book, Songs of Seoul: An Ethnography of Voice and Voicing in Christian South Korea (University of California Press, 2014), was awarded the Edward Sapir Book Prize by the Society for Linguistic Anthropology (Co-Winner, 2014, American Anthropological Association). Harkness's second book is titled Glossolalia and the Problem of Language (University of Chicago Press, 2021). A number of his papers have been devoted to developing an anthropological approach to “qualia.” These papers incorporate the innovations of contemporary semiotics into the ethnographic theorization of sensuous social life. Recently, Professor Zhao Xingzhi (Sichuan University) and Professor Xue Chen (University of Electronic Science and Technology of China), on behalf of Signs & Media, had the honour to interview Professor Harkness on various questions related to linguistic and semiotic anthropology.

Zhao Xingzhi (hereinafter Zhao): From your first book Songs of Seoul: An Ethnography of Voice and Voicing in Christian South Korea (2014) to your second book Glossolalia and The Problem of Language (2021), we can find that voice, sound, language, and qualia are the keywords in your research. How do you, as an anthropologist, become interested in those topics?

Nicholas Harkness (hereinafter Harkness): First of all, thank you for taking the time to read my work and discuss it with me. It has been a great pleasure to get to know you both during your stay here at Harvard this year.

Regarding your question, I suppose I always have been interested in these topics, even though I didn’t always have the lexicon to describe this interest with any precision. This is probably especially the case for the problem of qualia. I came to my specifically anthropological interest in these things quite accidentally. Having sung actively since I was a child, I was interested in the role of voice, speech, and song in culture. This interest led me to the anthropology of language and music, which led me to South Korea, where singing plays a very prominent role in social life. In South Korea, I began with schools of music and eventually found myself conducting ethnographic fieldwork in Protestant Churches. As you know, South Korea is widely known for the massive size of its Protestant congregations. In these dynamic religious contexts, highly cultivated vocal practices, both spoken and sung, were fused with highly cultivated models of feeling, and qualia became an analytical and methodological solution to theorizing this connection.

Left:Harkness, N. (2014). Songs of Seoul: An Ethnography of Voice and Voicing in Christian South Korea. Berkeley: University of California Press.Right:Harkness, N. (2021). Glossolalia and the Problem of Language. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zhao: In Glossolalia, you define glossolalia as “cultural semiosis — sign behavior— that is said to contain, and therefore can be justified by, an ideological core of language, but in fact is produced at the ideological limits of language.” For the practices of glossolalia that you study in South Korea, you point out how “denotation,” or, crudely put, “words for things,” serves as an important ideological core of language thus as a powerful cultural concept mediating social relations (Harkness, 2021, p.7). Shall we say that understanding the role and effects of linguistic ideologies is also the goal of linguistic and semiotic anthropology? Could you please explain more about this point?

Harkness: I think this is a very good observation. Indeed, much of the focus of linguistic and semiotic anthropology has been to try to understand how linguistic ideologies shape and are produced by the relation between linguistic structure and linguistic practice. To consider the three together – structure, practice, ideology – is to consider, as my teacher Michael Silverstein put it, the “total linguistic fact.” The total linguistic fact gives us a sense for how the ideological line between language/non-language is drawn, and from there the ability to reach farther out into cultural semiosis to see where the sign/non-sign line is drawn. These lines are extremely generative for the organization of culture more generally. Glossolalia suppresses denotation, that is, suppresses what is widely treated as an ideological core of language, precisely in order to promise to deliver a kind of sanctified denotation. It builds the promise of language out of its negation. In this sense, glossolalia might be considered an intensified and exemplary case of the problematic that motivates the linguistic and semiotic anthropological program more generally.

Zhao: Many of your works have been devoted to developing an anthropological approach to “qualia.” How did you become interested in this field, shall we call it as, “qualia studies”?

Harkness: Just as glossolalia can often be a limit case for what people think of as linguistic, qualia are limit cases at the far reaches of what people generally think of as semiotic. They are semiotic encounters with a kind of suspended semiosis, that is, the feeling of encountering things “as they are.” The work I have done on this topic has been to demonstrate ethnographically how these limits are actually set and conceptualized through communicative interaction. I was led in this direction in during my PhD when Michael Silverstein responded to my request for a course on the anthropology of the senses by offering a seminar that explored the problem of qualia. Interestingly, during the seminar we never read a single publication with the word “qualia” in it. There, Lily Hope Chumley, with whom I published early work on qualia, and I, along with other students, began to develop and refine the semiotics of qualia for anthropological research in relation to our own ethnographic projects. When Lily and I returned from our fieldwork projects, we resumed our conversations about qualia. I suggested that we organize a conference in honor of the anthropologist Nancy Munn, the author of brilliant ethnography, The Fame of Gawa, and a pioneer in the serious incorporation of Peirce’s concept of the qualisign into an anthropological theory of value. Since Munn had not really investigated the qualia problem beyond a brief mention in her book, I suggested that we connect Silverstein’s qualia seminar with Munn’s book. The 2010 conference was titled “Qualia: Anthropological Explorations in the Experience of Quality,” and many of the papers were published in a 2013 special issue of Anthropological Theory. This series of events—the seminar, our fieldwork, the conference, and the special issue—really launched a larger program aimed at understanding the qualia problem through the specific conceptual and empirical commitments of linguistic and semiotic anthropology.

Xue Chen (hereinafter Xue): Such a remarkable experience! We understand that the term “qualia” is adopted from Charles Peirce’s semiotics, and you once pointed out that “Qualia provide a methodological link between general anthropological understandings of practice and a technical semiotic approach to pragmatics” (Harkness 2015). It seems that you take “qualia” as a good entry point that connect anthropology with semiotic studies.

Harkness: In linguistic anthropology, we have a foundational concept called metapragmatics, coined and theorized by Michael Silverstein. Pragmatics can be seen as pertaining to the phenomenon of indexicality. Indexicality is the concept necessary for the semiotic analysis of social action or practice. Metapragmatics is the concept necessary for explaining how indexical signs become constrained and directed in social life. It provides an indexically-oriented explanation for what Peirce referred to as “habit” and what Saussure tried to explain by positing langue. One of the problems facing the indexical theorization of social action is the tricky, shapeshifting, and methodologically difficult problem of the sensuous dimensions of practice—embodiment, feelings, and the subtle ways people orient to indeterminate quality spaces. Qualia, when conceptualized via Peirce as “facts of firstness,” allow us to see how indexical processes can produce their own semiotic limit in feelings of sensuous immediacy. This way, a semiotically formulated concept of qualia opens up a methodological pathway for the elements of practice, such as bodily disposition, that seem to resist – ideologically at least – analysis by traditional semiotic methods. At the same time, even though we talk about qualia as limit cases that seem to suspend semiosis in feelings of immediacy, they are nonetheless caught up in vast complexes of indexicality. The sensuous dimension of practice and the indexical constitution of pragmatics come together in an experiential point that feels naturalized and unmediated—in a sense fundamentally “true.” In this way, we can see the qualia problem more generally as an account of how culture shapes experience in such a way that it does not seem cultural.

Zhao: In Peirce’s semiotic phenomenology, he discussed the terms such as “quale”, “quality” or “qualia” in a purely abstract way. There were barely concrete examples in his manuscripts to support those concepts. However, you did a great job to develop those terms into the urban cultural studies, such as the “softness” in Soju and so on. In your opinion, why is it essential to reactivate the “qualia” in sociocultural studies today?

Harkness: As you suggest, Peirce’s semiotic project was really focused on inventing and refining conceptual instruments rather than carrying out empirical analysis. For the past half century or so, semiotically oriented linguistic anthropologists have been hard at work developing ethnographic methodologies and analytical approaches to understanding the indexical, that is, pragmatic and metapragmatic, constitution of social life, working outward from the problem of language. Much of this work has been aimed at trying to understand and explain the vast indexical processes that constitute and contextualized human communicative behavior, and to figure out how to conceptualize and situate language within this broader semiotic framing. Clearly, this project sometimes requires updating or even reformulating some of Peirce’s ideas. My work on the qualia problem continues this tradition and tries to push these insights even further. In a forthcoming paper, “Qualia, Semiotic Categories, and Sensuous Truth,” I posit the semiotic rubric of “Rhematics,” which extends our knowledge of pragmatics and metapragmatics into to the domain of qualities – that is, from secondness to firstness – and the semiotic processes that orient to qualia as “facts of firstness.”

Charles Sanders Peirce(1839-1914)

Xue: You also point out that in anthropology of qualia much of the problem revolves how culture shapes experience in such a way that it does not seem cultural. It is a remarkably interesting point. Could you please further explain this idea?

Harkness: Apart from Peirce, much of the modern intellectual history of treatments of qualia has largely oscillated between rather statically realist or nominalist positions – that is, as either perceptual variations in sensory experience or subjective interiors conforming to radical forms of individuated consciousness. For both sides, qualia seem as real as they can seem for an individual. Anthropologists are certainly interested in these question, but much more from the point of view of the semiotics of social groups. That is, we tend to ask first about the social constitution of experience—whether terms are “sensory” or “subjective.” And when we have tried to give a name to that which constitutes a social group’s semiotic presuppositions and expectations – and by extension the semiotics that seems to differentiate one group’s “way” from another – it has often been the word “culture.” The qualia problem focuses on how social groups constitute themselves through feelings of what there is to experience, what feels natural and true, even what largely goes unremarked or unreflected upon. Clearly there are other approaches to this problem (Bourdieu’s notion of habitus, for example, comes to mind). Peirce helpfully used the term “sensuous” rather than “sensory,” which, in English at least, gets us closer to the felt experience of a kind of vivid truth without reducing it to the perceptual, bodily questions of “the senses.” Qualia can pertain as much to the feeling of thought as to the feeling of the skin. This is a long-winded and meandering way of answering your question: to say that qualia pertain to a cultural process that shapes cultural experience in a way that makes it seem not cultural, is to say that, by definition, qualia erase the semiotic conditions of their production. As cultural emergents, they form a semiotic limit case of the mediation of culture.

Zhao: Qualia seems to be relevant to ideas such as feeling, affect, materiality, and embodiment. Compared with those existent ideas in anthropology, why does the problem of “qualia” increasingly become as one of the most critical issues today?

Harkness: The concepts of embodiment, materiality, senses, and feeling are vital for navigating a whole domain of sociocultural experience. But as analytical categories, they often fall apart, because built into them is a reliance on something outside of semiosis, some pre-semiotic authority that might be located in bodies, matter, perceptual channels, and affect. If one is committed to pursuing these questions through a semiotics of cultural mediation, then then you eventually run into a certain kind of analytical problem with these terms. But if one pursues these other concepts through the problematics of semiotics, and one pursues the problematics of semiotics through careful consideration of language, then one can begin to draw a powerful connections all the way from something like qualia which seems – and let me stress the word “seems” again – to stand outside of semiosis to something that is robustly and unavoidably semiotic, such as language, without forcing a wedge between the two.

Zhao: Now I suggest switching our focus to some more general questions on linguistic and semiotic anthropology. Is “language” still the essential problem in semiotic anthropology today?

Harkness: That's a good question. There are many anthropologists who will accept the label “semiotic anthropologist” but not “linguistic anthropologist.” And there are plenty of linguistic anthropologists who would not accept the label of “semiotic anthropologist.” So, there's still a kind of division of labor between these two throughout the field. I tend to think that language remains so important for the anthropological enterprise because of its unique semiotic properties—in particular, its systematicity as a symbolic system (and hence denotation being a widespread ideological core). It also is the medium through which most ethnographic data is generated and practically all scholarship is formulated and disseminated. The challenge is to work one’s way out of language, carefully, while not losing sight of it, as one moves into relatively non-linguistic areas of semiotic analysis. The ideological boundary between language and non-language is an exciting one! And it is the anchor that we need to be able to further explore the ideological boundary between signs and non-signs. By keeping this in mind, the field has been able to address major questions and problems in linguistics and sociolinguistics, but also in sociocultural anthropology as well, and its various past attempts at theorizing “meaning.” These attempts include such as in the legacies of mid-century structuralism, which, despite some really brilliant insights, was basically an extension of phonology onto everything else, even though, as Jakobson pointed out, phonology is one of language’s most unique features and probably not a good candidate for a model of the analyses beyond language. These attempts also include so-called “symbolic” anthropology which, like structuralism, also produced some brilliant insights, but as method and theory was a kind of grab-bag of interpretative approaches to pointing out how conventional signs function as vehicles of culture. Much of the field over the past 50 years has been laying out a method for moving beyond these approaches by asking how the underdeterminacy of sociocultural processes, constituted through indexical signs, becomes stabilized, presupposed, and even generative in the production of a metapragmatics of meaningfulness.

Xue: Similar with semiotic anthropology, semiotics today increasingly shifts its focus from text to context. Then, how do you think of the relationships between semiotics and semiotic anthropology? Are they on the same page since they both regard sociocultural phenomenon as the semiosis?

Harkness: It does seem to be the case that that they are increasingly on the same page. With the introduction of a working knowledge of indexicality into linguistic and semiotic anthropology, a methodological pathway has opened up to better understand the relation between the relatively textual and the relatively contextual, between the degrees of co-occurring intra-textual signals and the degrees of stability and variability across inter-textual events, between the processual dimensions of entextualization (and genre) and the typifying effects contextualization and enregisterment. I suspect that that the traditionally text-focused approach of semiotics and the traditionally context-focused approach of ethnographically committed anthropology have converged in part recently by jointly having to deal with the semiotics of digitally mediated social life, which requires both approaches if one is going to make any headway. The central point, I think, is that we have to work through indexicality, via the concepts of pragmatics and metapragmatics, in order to isolate and then analyze what seems to be relatively textual or contextual about any slice of social life.

Zhao: On the topic of indexicality, recently a view has emerged in Chinese semiotic circles that indexicality is the most pre-experiential semiosis, thus it is in fact the most fundamental and primary motivation. Accordingly, the order of semiotic motivations suggested by Peirce might be questioned.

Harkness: That’s a very interesting point, and I think it is attuned to the fact that indexicality is a kind of experiential first in the pragmatics of social life, even if it isn’t necessarily a logical first. Peirce’s semiotic doctrine, of course, was a logical one, built on a posited ontology of firstness, secondness, and thirdness, and elaborated through a conceptual, abductive combinatorics of possibility, redundancy, and elimination, with the aim of producing conceptual instruments for the analysis of all sign phenomena. Despite Peirce’s very empirical work as a scientist, such as calibrating pendulums for gravimetric analysis and establishing the absolute measurement of the meter through the wavelength of a spectral line, his semiotic doctrine was really just that: a doctrine, the theoretical and potentially empirical consequences of which were not at the time totally clear. As he put it to Lady Welby, if I can paraphrase, the pursuit is not to find out what a sign “is” but rather what a sign “ought to be.” These days, we are now very much in the thick of the theoretical and empirical consequences of Peirce’s semiotic doctrine. Since Michael Silverstein’s groundbreaking 1976 article, “Shifters, Linguistic Categories, and Cultural Description,” semiotically informed linguistic anthropology has oriented increasingly toward metapragmatics as the overarching and most effective framework of theory and analysis. And this framework treats indexicality as a first principle of this social science. So, in Peircean terms, the ontological categories of firstness and thirdness can remain intact as categories defined both by their independent attributes and, crucially, by their degrees of logical dependency on one another. But methodologically, Peircean firstness and thirdness must be treated as derived categories, posited and projected from an analysis of secondness in the first instance, and in particular, of indexicality. Peirce’s discussion of the concept of the “fact” (CP 1.427ff) anticipates this, I think. And for the past 50 years or so, much of linguistic and semiotic anthropology has been working on the secondness-thirdness relation, that is, asking how token relates to type, how parole relates to langue, how message relates to code, how the dynamic and variable pragmatics of social life relate to the metapragmatics of sociocultural continuity and change. In other words, how the under-determinacy and volatility of the index becomes determined and regimented institutionally and over time. With the emergence of the qualia project, we expand the empirical agenda to firstness, extending methodologically from the pragmatics-symbolics dialectic to the feeling-laden, sensuously saturated domain of rhematics, the world of tone, and the semiotics that link sensuously unitary representamena to object spaces of qualitative possibly. This development has been made possible only by first establishing a careful working knowledge of indexicality as a methodological—and, as you say, experiential—first step.

Roman Jakobson(1896—1982)

Xue: Harvard University has a strong tradition of linguistic and semiotic anthropology. You have done a great deal to keep this intellectual tradition alive and prominent.For instance, the Roman Jakobson Symposium since 2019 initiated by you has achieved a great success and will continuously be of inspirations. What is your motive to organize symposium?

Harkness: Thank you for mentioning these efforts. Indeed, some of the most influential theorists of language and semiosis have been associated with this university, for instance, Charles Peirce was an alumnus, Roman Jakobson was a professor, and Michel Silverstein received his PhD from this university. When I started my position here in the Department of Anthropology a little over a decade ago, my senior colleague, Professor Steve Caton, had been carrying the torch of a semiotically informed linguistic anthropology. And before him, Professor Stanley Tambiah, who wrote some very influential papers on the semiotics of ritual and performative action, had been teaching in the department since the 1970s. But there wasn’t a strong emphasis on linguistic or semiotic anthropology as fields of research or training. I initiated the Roman Jakobson Symposium – and thank you both for participating this year! – to develop more interest and activity in this field, and to memorialize its distinguished tradition at Harvard. As a former Harvard faculty member, a groundbreaking linguist, a crucial bridge between Saussurean semiology and Peircean semiotics, and a vastly influential teacher and scholar, Jakobson seemed like good banner to help set the intellectual agenda for this new phase of Harvard’s relationship to language and semiotics. And I am so glad that you two are now a part of this history.

微信公众号二维码

微信公众号二维码

微信公众号二维码

微信公众号二维码